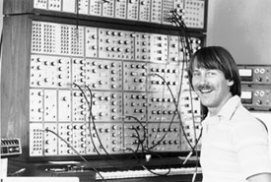

Dave Rossum has been designing synthesizers and audio electronics for over 45 years – as a co-founder of E-Mu Systems, as Chief Scientist at Creative Labs, and, more recently, as a co-founder of Rossum Electro-Music.

In that time, Rossum helped create classics like the E-Mu Modular System, the Emulator & Emax lines of samplers, the SP-12 and SP-1200 sampling drum machines, the Proteus sound modules and more.

In addition, Rossum developed technologies used in other synths, including the Oberheim 4-Voice and Sequential Circuits’ Prophet 5, and designed integrated circuit chips for Solid State Micro Technology for Music, which are used in a wide variety of electronic music gear.

This interview is one in a series, produced in collaboration with Darwin Grosse of the Art + Music + Technology podcast. In this interview, Darwin talks with Dave Rossum about The Art Of Synthesizer Design. You can listen to the audio version of the interview below or on the A+M+T site:

Darwin Grosse: Today, I have the great pleasure of talking to somebody who is an integral part of my history in electronic music. He’s been involved in so many pieces of the puzzle that were like building blocks for our industry and our kind of music. Dave, how are you doing today?

Dave Rossum: I’m doing great, Darwin.

Darwin Grosse: Thank you so much for taking the time out of your schedule to talk. Why don’t we start off by having you talk a little bit about what you’re currently doing?

Dave Rossum: Right now, we’re just finishing up the release of the Satellite module, that’s a follow on to our Control Forge module in Eurorack. Satellite is a less expensive and smaller front panel module with pretty much the same functionality (as the Control Forge), but without the programming interface.

Dave Rossum: Right now, we’re just finishing up the release of the Satellite module, that’s a follow on to our Control Forge module in Eurorack. Satellite is a less expensive and smaller front panel module with pretty much the same functionality (as the Control Forge), but without the programming interface.

It always surprises me how much time it takes to do all the documentation and get everything ready for that last little release. I think that’s the nature of engineering is that the last 5% takes 50% of the time.

Darwin Grosse: Now, for people that aren’t familiar, this is with your new company, Rossum Electro-Music, right?

Dave Rossum: Right. We started the company up couple of years ago. When we first started, we weren’t sure what market we were going to go into but went down to NAMM and observed two things. One was that the Eurorack market was taking off and the second thing is that everybody was just delighted with the idea that I might get into it. With such a popular community and such a great reception, how could we say no?

That was the direction we decided to take the company, and we’ve put together four modules now that are in production.

Since you’re asking what am I really focusing on, I’m really focusing on the fifth module, which is going to be called Assimil8or. It’s a sampler for Eurorack.

It’s quite a complex project and I’ve just really been working my butt off, getting up the basic drivers for the computer that is in that. It’s a remarkable challenge to get that bottom level infrastructure, so that everything is working perfectly. Then my software guy, Bob Bliss – who’s recently joined the Rossum Electro partnership – will take a lot of it from there, and put on the interface, while I work on the DSP stuff.

Darwin Grosse: It’s interesting that you are doing the Euro modules, because that’s the great big cycle of life for you, since you started E-MU doing modules.

Dave Rossum: It amazed me how far the pendulum has swung back. Back in the early 80s, when the digital synthesizer came in, we started making the Emulator. The modular sales just crashed and, while we were very proud of our modular system, we just couldn’t sell any of them to save our souls. We eventually transferred off the inventory to other people.

I never expected at that time that I would see it back again.

Then, in the early 2000s, when the computer platform started taking over, I was never that much of a fan of it, because I love designing musical instruments that people can touch and have a visual and tactile sense. To throw it onto a general purpose computer and put it all in a GUI….I couldn’t get that much behind it.

I felt that I couldn’t be the only person that felt that way, so I figured the pendulum would swing back. But to come all the way back to modular, it’s just a delight for me!

Darwin Grosse: I bet it is.

You mentioned the Assimil8or sampler. I have not seen a module with this level of buzz in a long time. People are really salivating over the prospect of you bringing this to play.

You mentioned the Assimil8or sampler. I have not seen a module with this level of buzz in a long time. People are really salivating over the prospect of you bringing this to play.

Based on the images and conceptual stuff that you’ve shared, it seems to combine so many different things from your background. It’s a patchpoint-filled device, but it’s a sampler. And, it’s unabashedly digital, but it has all of this interface control. It seems like it is kind of a combination of all the different things you’ve had your fingers in over the years.

Dave Rossum: It’s been a lot of fun, along with the idea of including the analog phase modulation into it. I’ve been delighted that it’s worked out so well. I want to throw something new in anything that I make.

When we first started in Eurorack, people thought we just remake the old E-MU modular. I already did that!

Because the modular has its own paradigm, even though I’ve done so many samplers in my past, making one — that is really appealing. First of all, just as a module and then also trying to get my head around, “Who are the Eurorack customers and what do they think is fun?”

It’s not your traditional music. My purpose in life is to delight musicians with new tools. So, being able to learn how they think and come up with stuff that’s going to excite them, that’s really what makes my day.

Darwin Grosse: It’s interesting you see it that way: that your job or your mission is to delight musicians. I think if we take a look at the history of gear that you put together, you’ve certainly accomplished that!

I’ll never forget the first time I ran across an Emulator. I cried. I just had so much joy from interacting with that thing!

To this day, there are people that view some of the early drum machines as a critical part of their voice. Clearly, with that kind of stuff, you found a way to resonate with musicians.

Background

Now, I’m curious, are you a musician yourself?

Dave Rossum: No, I’m not.

My brother is a talented musician. John would have been in the Jefferson Airplane, if he hadn’t gotten drafted. He was taking lessons and occasionally performing with Paul Kantner and Jorma Kaukonen just before they formed the band. John plays multiple instruments very well. I always looked up to him.

But my father was very much a scientist. [And] Dad had been brought up believing that the reason that he didn’t have a father in his household when he grew up was that his father was a musician and a drunk. Dad never liked music very much because his father was a musician and wasn’t there for him.

Later on, Dad learned that it wasn’t because he was a musician and a drunk – it was because he was two-timing my grandmother and had three children by another woman.

Darwin Grosse: Oh my goodness!

Dave Rossum: By then, everything had been set in place.

I grew up in this interesting relationship with music that I wanted my Dad’s love and he didn’t like music. So I hid my affinity for music. We had a piano for a while in the house and then an organ, because my mom would play. I would sneak down when nobody was in the house and noodle out tunes on these things, but I never took any formal lessons. My brother tried to teach me guitar but I was too much into the science stuff, so I never did that.

I never would have guessed in my teen years that I’d go into music. It was just so far off the radar. Even as I was doing graduate work in biology, the story has been told many times of me discovering the Moog synthesizer at UC Santa Cruz. And just suddenly, my whole life changed and I wanted to build synthesizers.

I have no idea why that crystallized so suddenly, but it certainly has to be all tangled up in this musical talent.

I had perfect pitch as a kid. I can tell that I still have a very good sense of pitch and a very good sense of rhythm, just naturally. I understand from scientific studies that those have a genetic component. I have music in my blood – but not in my upbringing – because of Dad not liking music and being a scientist.

Then the other funny thing is, as a kid, I was always an entrepreneur. It’s not very surprising that I ended up starting my own company. I was always trying to put together companies and make stuff and sell it as a kid, that was pretty obvious.

Darwin Grosse: You getting started building modules… were you drawn into it by someone else?

Dave Rossum: I was not drawn into it by anybody else – I was the leader of the group. In my teen years, I showed quite a bit of leadership capability. I’m also a mountaineer and so I was leading mountaineering trips with kids that were five or six years older than me, (but they) all looked up to me as the leader of the group.

Taking a leadership position again was very natural for me in this group of kids down at Caltech. Then some other people joined up at UC Santa Cruz who were interested in synthesizers. I became the crystallization point for that.

But also I was just a dynamo of energy, I was working on it like crazy and so on and so forth. Steve Gabriel and Jim Ketcham were two electrical engineers at Caltech who got me started learning electronics. I understood computers, but I really didn’t understand electronics. The two of them fostered me along my way, until I could begin to learn on my own. They long since went back to school and have had careers of their own.

I can’t look at anybody else and say, “They inspired me,” other than the kind of distant things, I mean, certainly Bob Moog, I always consider an inspiration. I got to know him and he was just a wonderful man. I had the pleasure of knowing Don Buchla in his later years, when Don got a little less afraid of knowing people who are also in the business. He was also very, very friendly and very warm. It’s pretty neat.

Darwin Grosse: At the start of E-MU, what was your initial product line? Did you come out of the gate with a full system? Did you start off with bits and pieces?

Dave Rossum: The first thing we tried, this was in spring of 1971. Jim Ketcham, this guy at Caltech, he was from San Diego and he heard that the San Diego Unified School District wanted to use synthesizers for getting kids interested in music in high school. They were putting out to bid for buying a bunch of synthesizers.

We didn’t know what we’re doing. We had no clue about business or anything like that. But we designed a prototype synthesizer., which we called the Black Mariah, to bring down and show it to the school purchasing department to see if we can get them to hire us to build synthesizers.

We had no track record, so of course they wouldn’t hire us. Didn’t even know about such things back then. And the Black Mariah was a horrible synthesizer!

We ultimately threw it out the library window of Dabney House. That was the first product!

Then, over the summer of 1971, Jim and Steve Gabriel and myself and three students from UC Santa Cruz (Paula Butler, Marc Danziger and Mark Nilsen), we all lived communally and put together a self-contained synthesizer. It was sort of copied, in at least in the essence, after the ARP 2600, which is about that same vintage.

We had seen that idea, we decided that fixed front panel synthesizer was the way we wanted to go at that time. That was called the E-MU 25. Two of those were built, I don’t think either one of them still exists. One ended up down in L.A. in some project people’s hands.

The other was in the Museum of Conceptual Art in San Francisco, the last time I saw it, which I think was in the late 70s. I don’t know where it’s gone from there or if it’s just in trash. Both of those have disappeared.

After that summer of ’71, the guys from Caltech went back to get their degrees. I met up with (future E-Mu president) Scott Wedge. He’d been a friend in high school and the two of us, along with my girlfriend at the time, Paula Butler, decided we’ll go ahead, and we negotiated with the Caltech guys and kept the name ‘E-MU Systems.’ And I moved forward, completely redoing all the technology.

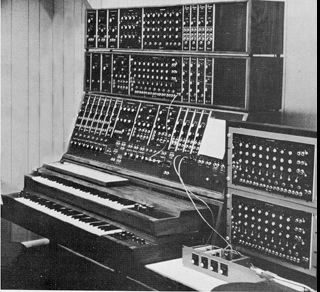

We decided we wanted to build a real modular system. We clearly had gotten circuitry that was equal to or superior to what ARP and Moog were doing at the time, so we thought we could compete in the modular marketplace. That was the birth of the E-MU modular. March of 1973 is when we delivered the first one of those. That stayed a product all the way through early 1980s.

Darwin Grosse: So, you came out of a gate with a full synthesizer worth of modules then, right?

Dave Rossum: Yeah – we had a pretty good road map. Like Moog and ARP, we were in that ‘East Coast’ school, as it’s called now, even though we were about as far for the West Coast we could get in Santa Cruz [California].

We knew the kind of modules we wanted to do. We tried to be somewhat innovative with a number of features on them.

In the summer of 1974, I went backpacking. I realized how much I’d missed taking vacations and Scott was very good at blessing my taking a month off and going with friends, a group from UC Santa Cruz, up to the High Sierra for a month. We’d been talking about, we hadn’t put a sequencer in the original E-MU modular and we weren’t sure what we were doing.

On that backpack trip, I suddenly got one of these flashes of inspiration: you could turn sequencers into a series of different modules, logic modules like and/or gates, separate the generation of the voltages from the counting of the steps, so [that] you had separate address generators and output modules. You could connect these things in interesting ways.

We came up with a modular sequencer, which I don’t think anybody has ever done since then. There might be little pieces in the Eurorack now. That was very innovative. Not that many people knew about it.

The E-MU modular was certainly much less popular and by the late 80s, the digital revolution had taken over. There were computer controlled sequencers, including E-MUs keyboard sequencer, the 4060 Polyphonic Keyboard. That modular sequencer was really a pretty interesting gadget.

Darwin Grosse: Now, to what extent have you taken some of those ideas? You now have the Control Forge, which is like a CV-generation tool. It’s a digital system, but were you able to bring some of those conceptual bits and pieces into that?

Dave Rossum: We really didn’t build it off of the modular sequencer. Certainly, the experiences and the fun of that as we worked, we thought about our experiences in the modular world that we brought into Eurorack.

The real genesis of the Control Forge was a piece out of the Morpheus module we built in 1993 at E-MU. The Control Forge portion of that had the rather ignominious name of ‘Function Generator.’ Niel Warren, he was relatively new to E-MU, but very much a genius and we tasked him with figuring out some way to make interesting control module contours for the Morpheus.

He created this conceptualization of thinking of any control module source as a series of segments which have a duration, they have a destination, they have a shape which is how they get from where they are now to the destination. Then they have decision points – during the time of the segment or at its end, [asking] “what do I do next?” With those four building blocks, you can create something that’s really practically arbitrarily complex.

Control Forge was an interesting module, because the idea in Morpheus was very simple. We thought this would be a “slam-dunk” module. Bob Bliss working with this back then, consulting with us, and as we started to work on the software, we kept thinking of more things that we could do. Everyone was like, “Yeah, if I were a programmer here I would really want this feature,” until the thing just expanded hugely with feature creep.

But we just couldn’t stop ourselves, because everything we think of we go, “Yeah, that’s really cool. People are going to love that.” And they have.

As people dig into [that] very deep module, we keep getting fan mail from people saying, “Oh, I just discovered this, this is so cool!” We’re very happy with the choice, but it took a lot longer to complete Control Forge than we’d initially thought. A lot of that is because, as you get into this module, we’re thinking you really want to embrace this idea, “I don’t want to put any constraints on the user, I want them to be able to do stuff that we haven’t dreamed of.” That’s the way we look at it.

The Emulator, Drumulator & Beyond

Darwin Grosse: From this modular genesis then, you ended up somehow making the Emulator and the SP series drum machines and stuff like that. How did you move from this real analog and real broken-apart system … into a purely digital realm, with relatively minimal patching interfaces?

Dave Rossum: Really, I’ve never looked at the question that way. That’s really interesting.

The evolutionary story – my background at Caltech, my degree is in biology. But [the] concept [of] what I wanted to do in biology was to apply computers to biology. Now it’s being done all the time, but back in 1970, that was a completely radical idea. I studied computer science as a minor at Caltech and was familiar with digital logic and things like that.

What I should say, too, is that, even at the very beginning, the E-MU keyboard, our first monophonic keyboard, was implemented digitally. It had digital logic in it, unlike the keyboards from the other manufacturers [of that time]. We were very comfortable with digital logic, but there were just no way you could do signal processing back in the early 70s.

In the late 70s, there started to be some capability of doing audio signal processing. We played with it in the lab, but everything we did just didn’t sound good. It didn’t sound as warm, as expressive as the analog technology. So our vision going into the 80s was the Audity – which was to be a computer-controlled analog synthesizer. It was very complex.

It was along the lines to the Prophet 5. In fact, Dave Smith came to us, and we helped him along quite a bit with developing the Prophet 5. It was kind of a “baby Audity,” but the Audity voice was about triple or quadruple the complexity of the Prophet 5 voice. The computer [of the Audity] was to be far more sophisticated, and so on.

That was the direction we were heading when again, Sequential switched over to the Curtis chips and, without telling us, suddenly we got a letter from them saying they weren’t going to pass royalties anymore, which is what we were expecting to finance the development of the Audity.

Necessity was the mother of invention. We had to come up with a product. We’d seen the Fairlight [CMI] at the AES show in May of 1980. We were just amazed at how fascinated people were with digital sampling, with the sample playback with pitch shift. We worked with Roger Linn — Roger Linn actually was a synthesizer programmer for Leon Russell, and Leon was our first big name sale of an E-MU modular. Roger was instrumental in making that sale. We’d stayed friends.

I actually did the design review on the LM-1 drum machine before Roger came out with it, to make sure there weren’t any obvious bugs in it and so on and so forth. We were familiar with digital sampling. It seemed like just very low hanging fruit.

I guess what I’d say is we ultimately knew that digital signal processing was the way for the future. It wasn’t really ready for full synthesis at that point, but when we needed a quick product, that idea of sampling where you don’t really need to do any signal processing, you’re just playing back a recording.

It turned out again, by total dumb luck, the sampler was the perfect thing to get into the marketplace with, because in those days, Moore’s law really didn’t apply so much to the computers. They weren’t evolving as fast as we see them now, but the memory was falling, and memory is what you need for samplers.

I could claim I had this brilliant foresight into how the world was going around, but that’s completely wrong. We just stumbled into it. We ended up making samplers at the time when – because the cost of memory kept declining and declining – sampling got more and more and more powerful, much [more] quick[ly] than any digital synthesis technology. We were lucky enough to be the dominant player in the sample sound market starting with the Emulator One.

Darwin Grosse: It was shockingly cheaper than the Fairlight and the other things that were available at the time. It blew people away, because it was like a third of the cost.

Dave Rossum: That was my innovation. I saw the Fairlight and I saw what they were doing. They were using a separate computer and a separate memory for each note that you play. I immediately thought, the separate memory is dumb, you want to play the same note when you play multiple notes on the keyboard. You don’t want to play the same sound usually so for god’s sake, share the memory. Then, you can just use DMA chips to shovel the sound out and then you only need one computer to run the whole thing.

Those were the innovations that allowed us to make the Emulator. It was actually about a quarter the price of an equivalently-configured Fairlight.

Then, there was a similar thing with the drum machine. Roger’s, the one after the LM-1 was the LinnDrum. Roger’s LinnDrum was $3,000. Again, he was using separate memories, separate controllers. You couldn’t use the same Emulator technology to build the drum machine, it wouldn’t make it that much cheaper. But there was a technology I learned at Caltech, called micro programming that allowed me to build a little tiny computer that could put all the drum sounds in the same memory and reduce the cost of the drum machine by a factor of three.

That came out of the really great education that I had at Caltech and just my own strong desire to innovate.

They both were groundbreaking products. I mean, the Drumulator, The one that everybody knows and love is the SP 1200, SP 12 family. I’m a grandfather of hip-hop! I’m actually very proud of that, I think it’s really cool. I actually really like good hip-hop, I think it’s just great music and again, was so unusual when it came around.

Darwin Grosse: I think it’s hard for people now to understand how basic computer technology and the availability of slightly bigger memory chips would cause the development of a whole new instrument. A slightly faster CPU, or a slightly more integrated memory system, all these things could make a tremendous change in the instruments that you create.

What I’m curious about is one of the things that was happening at the time, with these early digital systems – as they got better, there was a real radical change in what they sounded like too.

Some of it because you were going from very low bit count to higher bit counts. There wasn’t even really a set upon sampling rate that was considered good enough for whatever. Things like aliasing filters weren’t necessarily completely tweaked the way that we imagine now.

What were the things that, for you, represented what was important for the sound of these units?

Dave Rossum: You’re right, it’s very much a sense… a lot of it is a sense before you actually get to hear it. When we did the Emulator One, the Fairlight had 8-bit linear coding. There was no point in going to 16-bit storage and you couldn’t afford it.

There was no question we had to use 8-bit, so we used the companding DAC (digital-analog converter), a mu-law companding DAC. Roger used that in his drum machine. I played with it in the lab. I was familiar with it.

It sounded lousy, but it sounded less lousy than 8-bit linear, and that was the choice. We really didn’t feel we had much choice in that, but it was actually over Christmas vacation before the NAMM Show in 1981 when we introduced the Emulator and Stevie Wonder came in and hugged it at our booth and bought the first one — and so on and so forth.

We never really played with it before. I came in to work late one day, and Ed Rudnick and a guy named Ken Provost, who did mechanical design for us but also played the violin, had finally done a really good sampling session on a violin. I came in and they said, “You know, we really have something here, this is going to revolutionize.”

We were trying to get something that would make us some money, so that we could manage to pay the lawyers to deal with this mess with Sequential Circuits. It was this intuition that the companding deck could do it. Then the discovery that yeah, it would, and then the real big thing was a year later when the Emulator, we sold the first 20 of them. We planned to sell five a month, starting in July. July, August, September, October, those 20 sold.

We couldn’t sell November’s allocation or December’s allocation to save our soul. We almost sold all rights to the Emulator to another company, Music Technology. When we went to talk to them about maybe selling it, we could tell they had n’t any more of a clue how to sell it than we did, so there was hardly a point in giving them the rights.

Then we went to the 1982 NAMM show and we made three changes to the Emulator: we cut the price from 10,000 to $8,000; we added a sequencer; and we added to the sound library. Instead of giving five disks, we gave 25 disks.

In retrospect, it was that change of giving 20 more disks, with good sounds on it, that just opened the flood gate. Suddenly, we never had trouble selling Emulators after that. We could basically sell as many as we could reasonably produce until its end of life.

It is that sound, it’s the combination the musicians discovering how to use it and having that piece there.

The innovation we did in the Emulator 2, was where we did a differential encoding. I actually saw that circuit somewhere else, and thought, “I bet that’s really going to work, because it emphasizes high fidelity of the low frequency sounds, and gives your crappier fidelity at the very high frequencies.” But when you’re recording things like cymbals, you could put up with quantization noise and so on, and it doesn’t sound horrible. If you’ve got something with a lot of bass, that’s where you really want the warmth and the purity. Again – I saw the coding scheme, and it fit with how I comprehended sound.

The same thing with the Drumulator. [People] talked about the weird sampling rate of the Drumulator. That was not crafted down into the hertz, but we got about where to put it so that the aliasing frequencies were up in those pitches where actually you weren’t going to have enough fidelity with the sample rates that we could affordably produce in the thing to give you the real substance of the sound there, but you could fake it. You could substitute aliasing up there and the critical bands in your ear don’t have the sophistication to really tell the difference. So, you could hear the difference, but it sounds decent, it sounds good.

Darwin Grosse: I think it’s interesting the way you’re talking about this. You had already, by that time, been working with digital systems enough so that you could intuit what the sound would be, when you’d look at a coding scheme or technical concept. You’re in your head almost translating it into what it would sound like.

Dave Rossum: Exactly. This is something that I do. It’s not anything I can teach anybody, but somehow I’m just lucky enough to have a sense of what’s really going to sound good and be a good tool for the musicians.

It’s very intuitive, it’s very artistic. It isn’t a science. I can relate it to the scientific principles, but it’s much more than that.

Darwin Grosse: The next thing that really knocked people over was the development of the Proteus. I had several in my studio, and everybody I knew had several in their studios, as well. What was the groundbreaking thing with that?

Dave Rossum: We had the opportunity, the funding, and the technology had finally got there [so] that we could make a true mathematical interpolator. We could use the ideal mathematics for shifting the pitches of sounds, that was called the G-chip.

When Emulator III came out, it did not use this technology. It used the traditional Emulator technology. The memory, everyone wanted to put the memory in sockets, so we put the memory in sockets so that you could update. They were then memory SIMMs and [the manufacturer of] those SIMMs … sold us back stock that they knew had reliability issues.

E-MU was a little company, they probably thought we probably wouldn’t matter.

Well, reliability issues in touring machines are nightmare. The machines would just stop working mysteriously, and it took us months to figure out it was these sockets. We finally got the manufacturer to come clean and gave us all replacements. But by then, the damage was done.

E-MU had this huge hole in our revenue, so we needed [to use] the G-chip to make a product that [could go] as quick to market as we could. Not unlike with what happened with the Emulator. The product was originally called ‘The Plug’ – the plug to fill the hole in the revenue. Then, Band-in-a-Box got changed, the later code name for it was Bubba.

We didn’t expect the Proteus to be that fantastic, but what we discovered was this pitch-shifting algorithm that I designed. The seven point interpolation, with handcrafted interpolation filters that were tuned to my ear of my understanding of what you wanted to do in this, did this fabulous job of allowing you to just take the exact sample rate on each sound and you could cram this library or sound into a tiny space. 4 megabytes of ROM is what was inside of the Proteus. The project started in January or February and it wasn’t until November that we finally put all the sounds together, started listening to what they could do, and all of a sudden everybody got really excited. It’s like, “Okay, this thing is amazing.”

At the time, we had a relationship with Matsushita. We brought them over and showed them this thing that we knew was going to be amazing and asked them if they were interested. They said, “We already tried a product like that, nobody wants it.” The reason was because there was a critical mass point when you get enough really high-quality sounds in a box like that, suddenly you can do things that nobody ever did before. That’s what happened with the Proteus. The root cause of it was this interpolation algorithm I designed, but that then enabled us to create this product that had everything everybody needed to truly make music out of a box.

(E-Mu Director of Marketing) Marco Alpert told us, about a year after that, that we just changed the way the world makes music. And that really was true.

Sampling is now such an integral part of music, and it wasn’t [that way] until the Proteus. There were little enclaves around the Emulators, but now everything uses that technology.

Darwin Grosse: Right, it’s amazing. At the time, it was like the Proteus 1, and then shortly after the Proteus 2, which had orchestral sounds came out, then the 3, which is world instruments. All building off of this pitch-shifting algorithm which really was quite amazing.

It’s hard to imagine now the number of sounds, the number of presets that were built off of that tiny bit of memory.

Dave Rossum: I had the pleasure of demoing the Proteus to Bob Moog at that first NAMM show and his last question was “How much memory did you say in this?” I said four megabytes and he just shook his head. He was like, “I can’t believe that.”

Darwin Grosse: Another thing I think people don’t really understand anymore is the way that you would market the synths, so that you would get in Keyboard magazine three months later, so hopefully you were pretty close to manufacturing so that would drive the desire factor for your device. Right?

Dave Rossum: Right.

Darwin Grosse: I think you guys ended up running into some manufacturing problems or something that slowed the release down. It went from people being really excited about it to being like, “Where are these things? I have projects to finish!”

Dave Rossum: The Proteus ran into two horrendous problems.

The first thing was that, as I had mentioned, there was a multiplier that suddenly became available that allowed me to design this chip. As we went into production on the chip, we got the prototype batch and they were perfect. We got the next batch and all of sudden the people who made it said, “There’s a problem in this chip. They are drawing too much current.”

They said, “Let’s build another batch and see if it’s just a problem with the process.” So, they built another batch, and another six weeks of turnaround — and they had the same problem.

Then they started digging through, trying to figure out what it was, and it turned out that somehow our chip got built with a version of this multiplier that had a design rule violation. When they found the design rule violation, somehow they didn’t note that, “we made this chip for E-MU that had it.”

Now we announced [the Proteus] in January, and we had enough from the very first batch to make 3,000 or 4,000 Proteus, but that was about it. And the demand was much, much higher than that. Now we’re into October, and the batch is supposed to come out [at] the end of October. We’re getting 20 or 30,000 pieces made of this stuff and what happens?

We get the Loma Prieta earthquake here in California and that screws everything up.

Darwin Grosse: Unreal.

Dave Rossum: Unreal, yeah. I think E-MU might have been a very different company if those things did not happen and we’d been able to ramp up production the way we thought we could when we had such a hit. I don’t think the Sound Canvas would have ever caught up to us.

Darwin Grosse: You also came out with the Morpheus, and then I think was it the Ultra Proteus that was built off of that? It had an amazing new control modulation system. For one of my good friends, Nick Rothwell, the next several years of his life were just dedicated to wrapping his head around that.

Was that related to a technology becoming available, or was that a pure design effort on your team’s part?

Dave Rossum: When I conceived the G-chip, I knew I also wanted to create a digital filter chip. Again, one of these lightning bolts of inspiration, [when] I was off skiing. Scott Wedge used to say, “You want Dave to invent something? Send him on vacation.”

I was off skiing, and all of a sudden [the idea of] how to build a high quality digital filter just all came together. I actually took a day off skiing. It wasn’t particularly good weather that day and I just sat there and pushed pencil on paper, and satisfied myself that “Yes, I actually invented a new kind of filter.” I’ve actually since found that other people had thought of it, but nobody really realized what it would do.

And that became what we call the H-chip.

The H-chip was a digital filter chip, originally conceived just to allow us to put a low pass filter like the traditional, the analog filter we put on the samplers. But, as I got familiar with what this digital filter technology could do and worked with my friend Dana Massie on it, we realized that, using this technology, we could make much more complex filters than just simple low passes.

So, we added that capability into the very first version of the chip. The Morpheus was the result of Dana’s continuing to push, [saying] “We got to come up with an instrument that can do this,” and my excitement about it. I really wanted to do it.

Then, the army of sound engineers – with the Proteus, they were the true heroes of the Proteus. They came up with just incredibly outrageous filter cubes, using this concept of the H-chip filter.

We loved the Morpheus, but it was such a cult instrument. Some of that was because you had all this capability, but you had this little two-line dot matrix, LCD display that you had to work through. So it was a very difficult instrument to grasp well enough to really grab the whole power. The people who did got huge rewards out of it, but it was quite a learning curve to get there.

Creative Times

Darwin Grosse: Now, roughly at this point, then, E-MU was bought up by Creative Labs. Was it because the company got in trouble? Was it just that an offer came through that was too good to be true, or both?

Dave Rossum: An interesting combination of those two things.

In 1989, we hired in a CEO and told him specifically what we’d like to do is get parentage for the company because we were pretty much self-funded. We had a few stockholders but we really didn’t have any significant capital.

We were riding the ups and downs of the marketplace so much. I always joke, but it is somewhat true, the hard part of the music market is your customers are always broke.

So, it was always a rollercoaster ride. We never had pockets deep enough so that we could just focus on bringing out instruments. We were always worrying, “Can we make payroll next week?” and so on.

Originally we thought of doing an IPO, but Kurzweil did their IPO in 1975 and then went bankrupt in 1980, and that pretty much poisoned the music market for anybody else doing an IPO.

So we were really looking for someone to acquire us.

Creative came around and we did a technology-sharing deal with them. We got to know them and really like them. And then they said, “We want to make an offer in buying the company.”

Charlie Askanas, our CEO, came to us quite secretly – you have to keep this thing secret because the securities rules and so on – and he said to Scott and me, “If this comes to pass, Creative is going to cut you up like a Christmas turkey, and you guys are going to be the least two popular guys in Santa Cruz.”

We told Charlie, we don’t know what they are going to say. Why don’t you go listen to their offer? He went over and listened to it and he came back just grinning from ear to ear.

He said, “I don’t believe it. What they said was, ‘We want to buy E-MU and leave the company exactly as it is. We just want access to the technology. We want to fund more technological development in the company, but we want to keep you in the music market doing exactly what you’re doing.’ ”

That was really music to our ears. The offer was a good one, so it all came together and we sold the company.

A lot of people don’t realize it, but that was in 1993 and many of the iconic musical instruments, like the Morpheus, had not been developed yet. [With] Morpheus, actually that final bit of development was under Creative. The E4 and the ESI and all those Proteus add-on modules and so on, those were all done under Creative.

People ask, what did lead to the demise of E-MU? Well, some of it was that Creative themselves, they were a sound card company. At one point, they were a two billion dollar company. They are now down to about 200 million dollar company, and that was the change in their marketplace. And, as a result, they were looking to save money. E-MU was just a fly speck for their financials, [but] they needed us to not be losing money.

The other thing that was happening was this transition from standalone digital instruments to general purpose computer platforms. I was never that interested in it.

Certainly, E-MU made the tries. The Emulator X and so on have been done for that, but we were never very good at that. It was really that transition in the marketplace that ultimately caused the decline of E-MU in the 2000s. But that was ten years pretty much after Creative had acquired us.

So it wasn’t the Creative acquisition that caused the trouble. It was E-MU’s own internal challenges and so on.

Going Euro With Rossum Electro-Music

Darwin Grosse: Okay, that gets us through the Creative period and you have this new business. You’ve come up with these new modules that you filled us in on the front end.

I [had] already become fascinated with the way you think about the designs of musical tools, so I’d like to hear a little bit about how you’re imagining, what’s the ‘through line’ on this series of modules that you’re coming up with?

Dave Rossum: Yeah, I’m not sure there’s a real through line at this point.

The first module we came up with, it’s called Evolution. It’s an all-analog module.

The first module we came up with, it’s called Evolution. It’s an all-analog module.

Its genesis, the E-MU modular low-pass filter, was a filter that I really liked. Somewhere in the web you can find and somebody quoting our filter that has the SSN-2040 in it I think, saying, “This is the filter Dave would have put in the E-MU modular if he had time.” But that wasn’t the case.

I never wanted to use the SSN-2040 in the E-MU module, because I love the sound of the original E-MU 1100, which is a discrete ladder filter à la Bob Moog’s [filter] with some twists.

When we first started out, I wanted to do something analog. I love that filter. As luck would have it, in some discussions with my partner Marco Alpert about what we might be able to do with it, he suggested maybe we could make it have a variable slope. I pointed out that ladder filters have a discrete number of poles that are either one, two, three, four and some number of poles so you really can’t voltage control that continuously.

Something that Scott Wedge, my partner at E-Mu, used to say was that, “Once Dave figures out it’s impossible, he’ll figure out how to do it in a couple of weeks.”

And that was what happened here. Once I told Marco, “You really can’t do both the controlled slope and the ladder filter,” I figured out a way to do it and prototyped it up one Saturday in the lab. And it sounded really cool.

That’s what we call our ‘Genus’ control, following the evolution theme of the module. It does this very interesting current stirring thing in an analog way, that just makes this kind of sparkly raindrop sound as you modulate it. Just something I found very audibly and musically pleasing. I think other people had, too, and then other than that, it’s just a very carefully done modern technology analog low pass ladder filter design.

I love the sound of it. I have a received the compliment by somebody would know that said, “Dave, congratulations. You finally outdone Bob Moog’s filter.” I took that as very high praise.

That was a lot of fun. The other modules thus far are all digitally-based, but I’d love to add analog modules when the inspirations strikes me.

The real thing we decided we wanted to do was to bring things that had pieces of the E-MU legacy into the Eurorack world. Also we’re innovative in some way that always I want to be – I’m an inventor, that’s part of my spirit. So I have to be inventing something. I just don’t want to pour things over into Eurorack.

Darwin Grosse: Regurgitate things, yeah.

Dave Rossum: I mean, if the business demanded, I might do it. We’ve actually talked about maybe we should. But that’s mechanical….it doesn’t sing to my heart.

Darwin Grosse: Right. One of the things you talked about is that your studies in school were sort of like the application of computing to biology. I’m curious to what extent some of that still lives in the kind of things you’re creating. Because when I look over your modules history, is that the Control Forge and the Satellite which the Satellite kind of takes Control Forge programs and allows you to run them separately, is that kind of right?

Dave Rossum: Yeah, the original idea is that you is you have Control Forge and several satellites.

I have that in my own little demo system and it’s just a delight for controlling the Morpheus.

Darwin Grosse: Right, and then you have the Morpheus, which is this multi or you call it a Z-Plane filter. I tend to think of it as kind of like a sort of morph-able filter in its own right.

Dave Rossum: Yeah, yeah, Z-Plane is a marketing name. It’s cute and it identifies it.

The key technologies in the Morpheus filter are not that the filter morphs but it’s the way that the filter morphs. That, as you vary those controls, they are changing the filter in a musically sensible way.

You can take a digital filter and change the filters, filter coefficients in real time and it changes. But…they won’t sweep smoothly from one filter to another the way you would hear as smooth. That technology is really the underlying magic of Morpheus.

Darwin Grosse: It seems like you’re not only looking for musical things but you also seemed to be drawn towards things that kind of have a movement, have an organic quality to them that’s really peculiar, particularly for digital designers.

Dave Rossum: I very much do think of the world in a biological and evolutionary way and when I think about sound it’s always in my awareness that it isn’t just the sound, it’s the human perception of sound. My understandings of how humans perceive sound, what’s significant to us and what isn’t, which to some extent is driven by my biological understandings of where humans came from. How and why [do] we have this tremendous ability to hear, and hear the tiniest distortions and the tiniest details in some ways, and yet [we] can’t notice other things that literally are quite dramatic, [because it] doesn’t make any difference to the sound to us? That all fits in with my process of deciding what compromises to make in engineering and what it is that’s going to be, as I said, a musically useful tool.

Darwin Grosse: It is interesting to think of the weird physiology and psychology behind hearing and how there’s not necessarily any direct correlation between the physics of sound and our perception of sound. It’s not always that clear cut and so I think it’s really interesting that that’s really at the heart of how you think about your designs.

Dave Rossum: Absolutely.

Looking Ahead

Darwin Grosse: I’m curious what kind of things are you exploring or at least hoping to explore in the future with your work?

Dave Rossum: As I said, I’m so deeply enmeshed in the sampler…that we haven’t thought that much in the future beyond that.

I personally think that, with the Morpheus technology, there’s a lot more that can be done with it [beyond] simply the Eurorack Morpheus module we’ve got right now. When I was developing and porting the filters from the E-MU Morpheus module over into our Eurorack module, I learned a number of things more about these concepts of morphing and what we termed the Z-Plane filter, some more innovations. I’d love to have the time to develop that deeper.

We worry a little bit about too many filters in our product line but I’m not sure. Being a lover of filters, I’m not sure you’re ever going to have too many filters.

Certainly, that’s something interesting and we love the Eurorack market. But I also have to say that I’m really open with Rossum Electro going beyond Eurorack. I don’t think we’ll stay just a Eurorack company, if the company continues to grow and thrive.

Where we’ll go after that is a little up in the air and I’m sorry I can’t really say more about it. I think the honest statement is we’re looking for innovation and I’ve been pretty open at trade shows. I’m saying, “Keep the cards and letters coming.”

We get a dozen letters every week saying, “Redo the SP 1200,” and that’s certainly on our radar. I think that’s something that very possibly we will do, although we haven’t really decided what that means yet. Again, that is something [that] is part of our history. It’s a very significant achievement and very popular even today. I love to keep my fans happy!

Darwin Grosse: Dave, I want to thank you so much for taking the time out of your busy schedule. It’s been fantastic hearing your story, catching up with where you are now.

I’m really excited to spend a little more time with your modules, too. I’m a huge modular-head, so I’m really excited to spend more time with them!

I want to thank you for this time, adding your voice to the history that we’ve been putting together here.

Dave Rossum: Thank you so much for putting together the interview, because it’s been a lot of fun telling the stories, and I try and tell them new each time. Hopefully I did okay job of that.

I’m really excited that you’re excited about the modules – I mean, that’s why I do it, is to get people excited about making music. Hearing that that’s still going on is just what keeps me going.

Darwin Grosse is the host of the Art + Music + Technology podcast, a series of interviews with artists, musicians and developers working the world of electronic music.

Darwin is the Director of Education and Customer Services at Cycling ’74 and was involved in the development of Max and Max For Live. He also developed the ArdCore Arduino-based synth module as his Masters Project in 2011, helping to pioneer open source/open hardware development in modular synthesis.

Darwin also has an active music career as a performer, producer/engineer and installation artist.

Images: Rossum Electro-Music, Wikipedia

For the love of all things synthy, please call him back and tell him synth players need a modern take on the polyphonic hardware sampler. I must stress, for keyboard players, not another phrase sampler like an MPC.

Just revamp the Emax/Emulator line: but use modern storage media like SSD or SD cards, instead of floppies. Complete with ADSR, filters, crossfade looping, velocity layers, and so on. Give it realistic polyphony, like around 128-256 voices. STEREO while you’re at it. Multiple outs, of course, as an option. To keep it modern, use a USB port, an make it import WAV files and use them natively.

The market is starving for this product *right now*.

A lot of us can’t stand using software samplers, and right now there is nothing available that meets or even remotely approaches the above specs. The only option is to buy a 20-year-old sampler with limited memory and old storage mediums (or install an exoensive HxC unit, but the small memory constraints are still there).

I second this suggestion.

Fantastic, thorough interview.

Awesome interview, would love to see a new synth with the zplane filter. Original morpheus still blows my mind!

Yep – amazing interview with a legend! Totally worth the read. Assimil8or sounds awesome. Drivers for the computer side of things make it sounds like it will have a great PC interface. Looking forward to seeing how that turns out. Exciting times ahead.

Morpheus was the first real synth I ever purchased with my own money. It was probably too much for a 15 year old but I was sooo proud of it. Still have it 20 something years later, still exploring it. Nothing else like it. Spent much of my youth drooling over many an Emax and Emulators but they were way out of my price range. The z-plane module may be the tipping point for starting a Eurorack of my own.

Dave is a good guy. And I’m glad he’s back in the industry. As for future instruments, here’s what I’d like them to make: a combination of the new sampler incl Z-Plane filter with the new analog filter, 6 or 8 voice desktop synth/sampler hybrid. With dual functions as a simple drum sampler (SP12 style) and a poly synth (Emulator style) with all the new bells and whistles. If you throw in a rompler in there I wouldn’t be mad either 🙂

Come on Dave! Less talk about modular and more talk about the return of Emu Sp1200. It cannot be that hard to make a modern workstation like Emu Sp1200 and especially now, when the SSM chips is re-made.

the interface is not that deep either and you should be able to make it with more features, but with the same concept (faders)

Don’t you think it has to be 12-bit, though? Or sample at multiple bitrates and bandwidths?

Interview was awesome! Thank you. It was so cool to hear about what went into the Proteus, Morpheus and how Emu was agreeingly bought by another company. That last piece of the puzzle was finally found. Thanks again.

Fantastic interview and great content… THIS is what Synthtopia is about! Thank you.

Fantastic guy. We need that old men showing us the future, as many of us are muss less capable doing such basic science. This software world is going to be hell for us and we yet see it coming. Assimil8or will be fantastic as all of their products are.

The ultraproteus was one of my favorite synths for many years, but this eurorack line of products does not click with me (especially control forge witch btw was my favorite feature on morpheus and ultraP). Also evolution as good as it sounds has that “bad” decision of cv over the slope. It doesn’t offer anything substantial really. Having all the slope outs available would be more useful for patching bp filters.

In any case these are nice quality products, but i would prefer if they did things outside the eurorack world which is packed with designers atm..

E-mu engineers were amazing working with just 16 mb of rom in the proteus modules. Think of the B3. Sounds awesome.

Great interview.