Any discussion of The Art Of Synthesizer Design would be incomplete without Axel Hartmann.

Hartmann and his company, Designbox, have handled industrial design for a Who’s Who of synth companies, helping to create classics like the Waldorf Wave & Blofeld; the Alesis Andromeda; the Hartmann Neuron; the Access Virus Polar; the Moog Little Phatty, Taurus and Voyager; the Arturia Origin, MiniBrute & MatrixBrute; the Studiologic Sledge; and the massive Schmidt Analog Synthesizer.

Hartmann’s work demonstrates that the industrial design of synthesizers deserves the same level of care and attention as the circuit or software design. Hartmann has raised the bar for synthesizers, with designs that are rational, easy to use and even beautiful.

In addition to his design work, Hartmann has also toured Europe as part the ABBA tribute band, AbbaKadabra,

This interview is one in a series, produced in collaboration with Darwin Grosse of the Art + Music + Technology podcast, focusing on The Art Of Synthesizer Design.

In this interview, Axel Hartmann talks about how he got into the industrial design of synthesizers, his thoughts on what makes a great synth design and the stories behind some of his best-known creations. You can listen to the audio version of the interview below or on the A+M+T site:

Darwin Grosse: I want to start of by asking you, first of all, if you could really quickly give a run down of some of the devices that you’ve worked on.

Axel Hartmann: I started out as an in-house designer at Waldorf Music.

That was back in 1989, and that was right after I finished university in Germany, where I studied industrial design.

It was Wolfgang Düren: he’s been the guy behind the PPG synthesizers, if you remember those from the ’80s. He’s been distributing those into the world and he was a very close friend of Wolfgang Palm.

In 1989, they were planning to do a synthesizer based on the PPG, which was the Microwave. I was searching for job back then, and they were searching for somebody who could help them with the design. So, it was a perfect match – my first approach into the music business or the business of building synthesizers.

I’ve been a musician and a synthesizer player for many years before that. I was starting to play in bands when I was 13 years old and I discovered synthesizers quickly after that.

I started to study industrial design with that in mind, that one day, I wanted to be able to merge those two interests of mine: making music and synthesizers, and industrial design. Working for Waldorf was the perfect chance to bring those two things together.

The Microwave was actually the first instrument that I designed.

From there, I still worked for Waldorf and even now after 28 years, all the instruments that you know from Waldorf music have been my designs. I work with them so I have the chance to stay with that company all through my career

While I was working for Waldorf, we realized the workload was not enough inside the company to really fill up my time. So, a few years after I started to work for Waldorf, I started to work for Steinberg and for Hohner and for MIDI Man. It wasn’t M-Audio back then, it was MIDI Man.

That came about because Wolfgang Düren, that guy who hired me for Waldorf, he was also distributing all those brands into Germany.

That was a perfect chance for me to also get in touch with all those companies. Novation, another one, but I’ve been working for them very early in the ’90’s.

Darwin Grosse: I was wondering how you went from being an in-house designer at Waldorf to be connected to so many companies. I didn’t realize that there was this side connection to all these companies.

Axel Hartmann: Yeah, that was how it all started. Wolfgang was very supportive and open for something like that. He said “Well, maybe we can use your services for these other companies too” – and in the end raise the budget to get me paid as well.

For me, that was a perfect way to interact with more companies, not just Waldorf, to get some experience in that domain, which was very good for me later, when I went away from Waldorf and started my own business with Stephan together.

Darwin Grosse: The Waldorf Microwave, when it came out… it looked stunningly different.

Axel Hartmann: Yeah.

Darwin Grosse: It was not the typical one rack high box with a LCD and a single knob and one button, or increment/decrement buttons. It looked classy. It looked like it has a design to it, and it looked like it had a bit of an attitude, right?

Axel Hartmann: Yes. Thank you.

Darwin Grosse: How hard was it for you to say “Let’s make something that looks different from everything else?,” because it was kind of shockingly different.

I think at the time, everybody assumed that musical instruments should be as unassuming as possible, and here you made something that kind of jumped off of a rack. How hard was it to make that decision? Or was that your natural aesthetic?

Axel Hartmann: Well, it was a decision that we all together took at Waldorf. This synthesizer, the Microwave, was something different back in those days anyway.

If you looked at the landscape of synthesizers back then, they were all like the Korg M-1. They were like 19′ devices, sample playback devices. There was a lot of different instruments, but not a real synthesizer coming back then, back in those days. Waldorf, they came up with this little PPG derivative back then, and that was something different. We tried to give these modules a look that speaks “I am different”, you know?

I did a lot of designs. Doing a 2D design for a rack mount, it’s not really a three dimensional thing. It’s more a graphic design that you put on the front panel, and we wanted something that stands out. If you build it somewhere, if you put it in a rack, we wanted that people can recognize, but just want them to see the red nose.

That was something that we all wanted. We wanted something recognizable. It’s just like Nord is doing their red. Not back then, but the red nose was something that was different, and it was also not just different, it was kind of sympathetic.

People always smiled when they saw the instrument because it was friendly. Still, it was very ergonomic. If you work with it, you find out the buttons that surround that monster knob, the big red one, they’re perfectly balanced and you can push them really nicely when you work with the machine.

We had the matrix on the right side, which also made it very easy to operate even if there has not been so many real knobs.

Darwin Grosse: I remember at the time, it was a time when I was obsessed with synth voice designing and stuff like that, and when it first came to a local music retailer, I was like “Oh, it’s interesting looking, but still just a knob and a couple of buttons.”

Then, they were always nice enough to allow me to sit down and spend time with it and I did, and I started doing a little bit of programming on it. First of all, the sound engine on it was so unique that you’re right. It was kind of a match; a very unique look went with a very unique sound, right?

Axel Hartmann: Yes.

Darwin Grosse: There seemed to be a coordination of efforts there, but also the user interface design was surprisingly adept, unlike so many boxes at the time. It was very comfortable to work on and if you think about how synthesizers work, you spend an awful lot of time with your hands on that panel, so just the layout of it, I was quickly adept with something that looked like it should have been harder to use than it was.

Axel Hartmann: That’s what we want, what we all wanted. The people working at Waldorf, they were all musicians. They still are, you know?

This is like many in our industry, if you cannot make it as a musician, you may end up working for PC electronics or somebody else.

Darwin Grosse: Right.

Axel Hartmann: Many of the people that you find there, some of them are great musicians. It was no different with Waldorf. Besides myself, there were a lot of trained musicians. Very skilled synthesizer players, developing those instruments and we knew exactly what to do to make a good workflow, even with just one knob.

Darwin Grosse: Well, from the Microwave, with Waldorf, you were involved in what is probably what people would consider the most beautiful synth ever made, which was the Wave. That synthesizer was, when I was coming up, everybody’s dream synth, because it had flip-up panels, reminiscent of the Minimoog.

It also had lots of controls, and it looked like it was going to be real conducive to real-time programming. It was as expensive as a car at the time, right?

Axel Hartmann: (laughing) Exactly. That was our own memorial thing. I remember well, we were literally working in a small house in a small village that’s name is Waldorf. This is why the company is called Waldorf. It’s in the Rhinelands. This company was so attached to the people living there and every now and then there was somebody from the village coming in and looking at what we were doing.

I remember this one guy who came in and he saw the prototype of the Wave sitting there and he said “This thing looks like this is able to kill Waldorf.” He was so right!

It was a much too big challenge for that small company. I think they spent all the money they could with the Microwave and put it in there, because it was a dream. It was a dream to do something like that.

But that was fun to work on. I remember that time – it was really nice teamwork. Really nice teamwork with Claudius Brüse. I don’t know if you’re familiar with that name. He’s a great sound designer. He works a lot for Hans Zimmer; he’s a fantastic musician and we together we did the layout for the user interface and we were configuring the modules and thinking how could those interact and work together.

There were two people, developers who were working on the sound engine. Actually, it was like two Microwave chips in there. They had an ASIC chip, built by Waldorf…for the Microwave and they put two of those into the Wave and analog filters. We made it big.

Back in those times, I also played the demos at the Musikmesse with that machine …

Darwin Grosse: That’s where I would’ve actually first met you then, because I used to go to Musikmesse all the time. That was one of my favorite things – to go and to just spend time with Waldorf there, because often it was quite improbable but beautiful stuff and amazing work. I guess I would’ve bumped into you then.

Axel Hartmann: I’m sure. I’m sure you did, because the first time at Musikmesse with the Wave, I did the demos.

I remember when I did that demo one day, there was Rick Wakeman coming in. I couldn’t play anymore because he was my hero! I had like a mental block! That was the funniest thing, you know?

Darwin Grosse: When I look over the list of things you’ve done, you’ve done a lot of important synths. You worked on the Alesis Andromeda, right?

Axel Hartmann: That’s right.

Darwin Grosse: And you’ve been involved with Arturia MatrixBrute?

Axel Hartmann: Yeah.

Darwin Grosse: You’ve been involved in some pretty physically huge synthesizers, and ones with a lot of user controls. Maybe this tells us a little bit about where your interests lie or what your desires are, because if I would pick those and say that these are sort of exemplars of some of your bigger works, it seems like you like a lot of controls. You like a lot of real time control on this stuff but you like a classy design as well.

It makes me wonder, what are the instruments that influenced you? You said that you were a synth player before you were a designer. What were the instruments that made you think about the design of instruments and kind of drove you towards wanting to build things that look like the Andromeda or the Neuron or some of these things?

Axel Hartmann: That’s a very interesting question.

If you look at the instruments I designed, they are not always exactly always my language because my clients, the people I work for, many of them have a very specific wish list and they have their own ideas of how they want their instrument to look. I bring in my taste, and my talent of organizing things.

What you can see in my portfolio is not always exactly what I would do, but I would do inside that team for that company.

What brought me to that spot is that people are calling me if they want to do a synthesizer; that’s a fantastic thing. It looks like the more synthesizers I do, the more I’m being recognized as this specialist in doing synthesizers so people keep calling me, which is very good and which I appreciate.

My personal favorite synthesizers are the ones that are probably yours as well. I’m a player. I’m not a Eurorack guy. I start to lose interest as soon as an instrument starts playing by itself.

I want to play it. I want to touch it, and I want to sculpt the sound, and I don’t want to feel like sitting in front of a telephone box and putting in cables. That’s not my personal favorite thing. I like what people do there, but the synthesizers I was playing with were like the Matrix 12. I love that design and I love the Prophet 5. All the classic synthesizers.

They all had their special taste and their special direction, so this is where I come from. I still like when I play for myself, I like to have a synthesizer with an easy-to-understand interface, not too much double functions, things where you can capture with one look where which function is. You recognize the functional groups instantly and it feels right.

These are things I also want to bring into the designs I offer my clients. They keep asking, they want their corporate design, but on the other hand I bring in the order and I try to do the best with their assets, if I can say so.

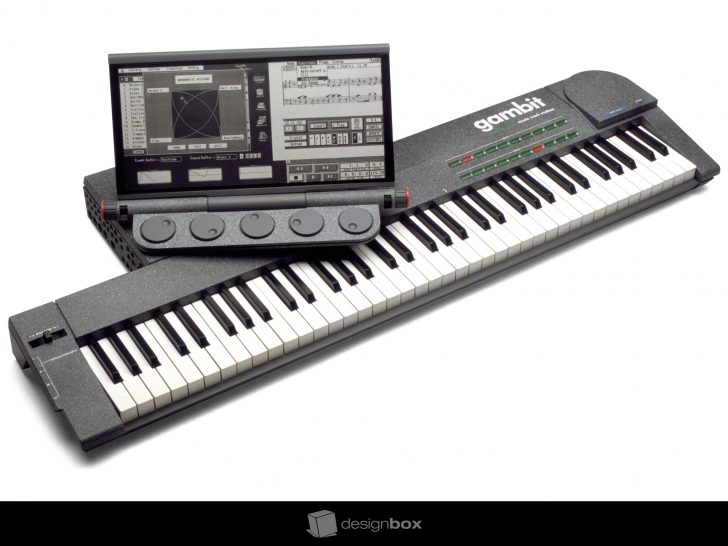

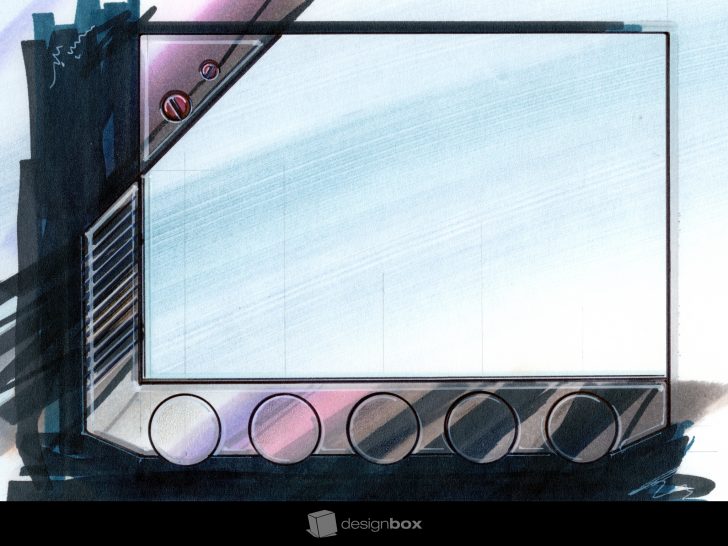

Axel Hartmann’s ‘Gambit’ Synth Design Concepts

Darwin Grosse: Well, its interesting because if I compared on the surface something like the design of the Andromeda and the design of say the MatrixBrute, would seem to be very different, except as you discussed this idea of having functional groups of controls.

Also, one of the things I noticed about your designs is that you find ways of drawing people to the most important parts of each control group. In the filter set, the filter cutoff, will often have some kind of distinctive thing, either color or size or something that will draw you to use it. Or in each case of functional groups you have a tendency to help draw people into the most used functionality. I think this is really pretty brilliant and it’s a neat way to work.

Now, what is the process you go through to iterate through designs until you get to that point? To the point where you feel like the function is right, and what is it that your designs actually look like? Do you work with modeling software on the computer? Do you take a cardboard box and put knobs on it and see what they feel like? What is the process of you going through the development of the feel of a synth?

Axel Hartmann: I’m not working alone here.

I have two people here that do just modeling, just 3D modeling, and they help me with three dimensional work out of an instrument or any kind of product.

With the synthesizer, if you’re looking at a user interface in the first place, it’s always 2D-ish. It’s always something that you look at and that you can also scribble. You place your different functions and everything. This is something that can be done easily in 2D.

For me, it’s always very important not only to have the structure of the user interface in front of me, but also the labeling; the artwork that comes with it. This is something that of the engineered synthesizers that you see on the market, they forget that the labeling is as important as the element itself.

This is why you see a lot of instruments in our domain that look kind of not right, because they’re not balanced.

It’s very important, from the first sketch that I do, that I always have in mind that there will be a product graphic around it. There needs to be space for that, so I start working in the 2D. I do scribbles and when I got a good set of scribbles, I start working with Adobe Illustrator and start to really work on the computer and place the different modules and functions and put them here and there and move that a little here, and move that a little there. Always working in kind of a grid.

If you ever designed user interface, you always know if you place one function, more functions come together and then you start rearranging and a lot of functions they go with it. You have to move a lot. This is a process that is very important – I love that process.

To arrange things and move things around and re-move them until I’m in a spot where I think that it looks balanced, it looks good. Then I take that and I go to Stephan Leitl, he’s my 3D designer. He’s helping me a lot. He’s sitting right there, right in front of me. We talk and I tell him what I want to have and what I want to see and he starts to implement all that into the 3D.

This is then when we would place the boards. We know a lot about how synthesizers are made up electronically, so we get all of the physical, virtual elements that make up the inside of an instrument as well. The connectors, everything that matters when you design something that really needs to be built later on.

This comes all together in the 3D system. From there, we create 2, 3 or 4 different versions of the design. That’s the first step that we do and this is something that we then show our client. The client will get photo-realistic pictures from the very start. He has a few versions that we show him, and he can then decide which one he likes best or thinks is best for him or his purpose.

This is the way we start working. If we find something, then we start rearranging and we’re trying to follow the process of the product development up to the point where it’s finished and can be built.

Darwin Grosse: How often do you get specific design goals and how often will the manufacturer bend their designs to fit your physical dimensions.

I’m thinking in terms of the voice boards and how big they are. Or the number of outputs and/or inputs and/or other connectors. Do they come to you and say “Okay, we’re going to have 2 audio ins, 4 audio outs, MIDI-DIN and make sure that that’s on the board somewhere?” Or do they expect you to initially make some judgements about that?

Do they come to you and say “Hey, our circuit board is going to be 20 x 7 inches and make sure it can fit in there”.

Axel Hartmann: Yes, that’s all possible, but this is the way it works. Most of the clients I’m working for, they know very well what they need. Many of them have already set up the basic boards.

We have the freedom then to maybe place the outputs and do the UI totally free. In some places, some clients are happy to receive our input even functionality-wise. We know a lot and we can also add our creative input to how a synthesizer could work.

Also, you know the Neuron story where we made the entire thing, so the entire sound generation system was our idea; my idea. This is something that the client sometimes also want when they call us and that kind of input. Not only the aesthetic design but also the real product design.

What do you want to bring to the surface? What kind of element could we bring to the surface that makes the user interested in the instrument? Things like that.

Darwin Grosse: That’s actually an interesting question though. From your perspective, what the company is going to want, is for you to design an instrument that’s going to make people want to buy it, right?

Axel Hartmann: Yeah.

Darwin Grosse: It’s probably the strongest argument for saying a black 1U Box is probably a poor design. There’s nothing about that that makes you desire to get off your chair and buy it.

What are the things that you’ve come to believe in, in terms of design, that help people want to get an instrument? What are the things that make them want to go to a music store and buy a piece of gear? And, what are the things that you think drive people away?

Axel Hartmann: If only it was so easy. It’s not that easy.

I think you know the guy Dirk Matten from SynthesizerStudio Bonn. It was one of the first synthesizer shops in Germany. He was selling Moogs and Oberheims and all the big synthesizers very early in the ’80’s, even in the ’70’s. We were talking a lot when I started to work at Waldorf and he always told me “Axel, people just want cool design”.

I never believed that, because I’m a believer into technology and I know that people also want the technology; they want something new, refreshing. Something that works differently that kind of tickles their nerves. They want to get into something new.

On the other hand, I think with a clever design, you can fulfill a lot of things that make a product attractive.

It’s simple, in one place it’s the physical design, how everything is made up and how it feels. But industrial design is also solving the problems of the manufacturer. It makes the product easy to produce, easy to ship, safe to ship. It doesn’t get worn too fast, it uses the same materials. These are all things that come together in a perfect design.

Besides that, big sound engine needs to be great and needs to be appealing. All the people want price breakers. Everybody wants a MiniBrute or a MicroBrute because they are so cheap. They’re still cool synthesizers.

If this all comes together, if you have a reasonable price, a nice package, good ergonomics, and a well sounding instrument; something that feels like an instrument you have a good product. People like this kind of product and they buy it.

Darwin Grosse: What about things that you think would drive people away? What are the things that you tend to stay away from?

Axel Hartmann: If you find something, from a designer’s standpoint, that looks and feels not right; it’s not well balanced. There are synthesizers out there or musical instruments that simply do not have the right user interface, wrong colors, the colors are strange.

We’re artists. We want to feel one with an instrument.

Why is a violin or a nice guitar so beautiful? You can have a totally ugly guitar that sounds much better than a good looking guitar, but the good looking guitar will always sell better, because it’s something that you buy for yourself that you want to be proud of.

Some instruments simply don’t look balanced – their too bulky, too chunky. I could tell you some, but I don’t because that’s not fair. But there are some instruments out there where I always go “How can they do that? It would be so easy to make it right.”

It costs the same in the production, but you need somebody to look at the different things. Sometimes it’s not even really bad design but maybe it’s bad design for that purpose.

Musicians have a different attitude. I was once working with a guy in Australia, Peter Vogel, who invented the Fairlight. He was a big fan of ‘ugly cool’. He always said “People who play these instruments that we love, the synthesizers, they tend to love things that are kind of ugly. They are kind of designed by need. What the engineer would do.”

This is not something that is always beautiful, but it’s engineered, and it’s also something that appeals to people. If you look at a Minimoog, it’s not aesthetically the most beautiful thing that you could think of as a musical instrument. But it was such a strong statement, so well engineered, so well brought together that it’s the icon. Everybody loves it. Understand what I mean?

Darwin Grosse: Yeah, I do and it’s actually interesting that you bring up the Minimoog because I would say that there’s a fair number of your designs – some of them I’m sure on purpose – that kind of hark back to the Minimoog. You had a chance to work with Moog on the Little Phatty, the Sub Phatty and the Sub 37, right?

Axel Hartmann: Right, exactly.

Darwin Grosse: I would say all of those, without being slavish, all kind of harken back to the Minimoog look. Was that something that they came to you with or did you say this is the natural execution?

Axel Hartmann: This is something that is a co-operation. I would never step too far away from being ‘Moog.’

Moog, they have such a strong corporate design. It’s the knobs, it’s the way the instruments look. They always have this quirkiness, and their perfectly balanced user interface is always clean and easy to dive into, easy to understand.

They have a natural talent to grab those parameters that you want on the panel, and the others they just leave them out. That’s a very natural, I would almost say a biological thing; it’s growing.

When I did design for Moog, I started with the Voyager. We had a booth with the Neuron side by side with Moog back then and Bob was still alive back then, and could use his name again. He was showing the Voyager; I saw this instrument and I saw the user interface was not right. It simply was not right and I asked him if he would give me the chance that I re-work that. That was my step into Moog.

I know exactly what to do if I work for Moog. They also have a very, very good marketing department. Emmy Parker, she’s a very strong person. She knows exactly where she wants to go with a brand. If I do a design for Moog, it’s always together with their Brand Director. They have very clear vision of how a Moog instrument must look like.

We need to link into that. We tried to bring in a new vibe, like we did with the Little Phatty with the swing back, the aluminum back. This was something that came from our side. This is something that carried their legacy in a beautiful way to support that legacy.

We always try to find something like that keeps the momentum of their brand visuals but adds something that compliments the basic idea in a very good way.

Darwin Grosse: Now, kind of swinging exactly 180 degrees, at one point I think in the mid 2000’s, you took the opportunity to design and actually manufacture a synth kind of completely from scratch, the Hartman Neuron.

The second time I would’ve seen you is doing demos of the Neuron, which I remember a lot of it was you playing the joystick and like really being able to wrangle the joystick a lot and use it for some pretty incredible on-the-fly sound manipulation. That was a case where you got to make all the decisions.

First of all, who did you have for collaboration on that and how hard was it when all of a sudden this was going to be your beast instead of a client’s beast?

Axel Hartmann: That was me in 2000, when I had the idea of a new synthesizing concept. I was on the search for somebody who could write the code for it.

The basic idea was to use a given sound and treat this like modeling in the 3D world: I wanted to model a sound. I wanted the sound model of a piano or a violin or of any instrument where you’re familiar with the sound. Then I wanted some handles on that, where I could just make the piano bigger. The violin, I could change the body from wood to metal – things like that.

I was searching for somebody who was able to do the software and I found Stephan Sprenger – Stephan Bernsee, now. He’s been the mastermind behind Prosoniq software, so he was inside the neural network domain. He told me that he was able to detect these things that I wanted to put handles on in the sound. He said his software was able to detect these points musically.

We started this corporation then in 2000, and we developed together this synthesizer. He was writing the code and we had a few people who worked on the user interface. We had some sound designers, people who gave us the samples like Ray Legnini. You may know him, he worked for Ensoniq back then.

We had the Yellow Tools people that gave us their samples, so those were the basic material we started to work on. During the process, we found out that the recognition of the sound attributes was very difficult to write and we ran into some obstacles there, but in the end we came up with this instrument that was a synthesizer.

For me, it was like working with sound by deconstructing the sound, by giving it a different attitude. This is how it ended. We understood a lot after we made that, why a piano looks like a piano and is made like a piano, because if you make it different it starts to sound really strange.

Darwin Grosse: As I recall, there were two difficulties with that device.

First of all, in order to manufacture, it ended up being quite an expensive device – similar to the Wave. It was one of those things where I wished I could have it, but knew I never could afford it.

The other thing is, when was that manufactured? Wasn’t it around like 2005 or 2006, something like that?

Axel Hartmann: 2005 was the end of the company already. It was manufactured between 2002 and 2005. There’s like 500 units living in this world.

Darwin Grosse: Isn’t it maybe true also that it just came at the wrong time? If it would have been a little bit later, things like the computer connection would have been easier to handle. Things like the built in electronics might have been more available or powerful enough to do some of those functions?

Axel Hartmann: Yeah, absolutely. I totally agree. I wouldn’t start the project anymore with the know how I have today, but this is how things are being born.

To start something like that, you need at least $1 million in your back pocket because it was a real huge development. We didn’t have that, even though Hans Zimmer stepped in at one point. He helped us a lot, at the beginning, but still we were always under pressure.

It was never really finished. This is probably the reason why it never really succeeded; we never had the time to work on it in a way that would have been appropriate.

It was too early, but if you do something like that, something really new, something innovative, you have to think ahead of your time.

How cool would it have been if we had SD hard drives? How cool would it had been if we had not 60 GB but a terabyte of data that we can load, a faster processor. All those things were like that back then and we were on the edge. The processor was behind, even if we had a fast processor, it was always too slow and not really capable. We were always on the edge regarding calculation power.

Darwin Grosse: In a way, some of the most innovative design, even if you go back to things like the MemoryMoog or some of these other things where they were just literally pushing the edge of technology. Sometimes good stuff happens even if it ends up being kind of devastating for the company that tries to take advantage of it.

In the end, you ended up with a software version of that; a plug-in version, correct?

Axel Hartmann: Right, right.

Darwin Grosse: Was that your first dive into working on software or had you done software designs before that?

Axel Hartmann: I did software designs before that, several. I would have to check what it was, but I did some for Steinberg and we did some software synths before.

Actually that software version, it didn’t want to be some follow up product. It wanted to be a product that could fill our budget so that we could really keep on developing the technology. That was coming out already when we were on the brink, where we were running out of money and people wanted money back, so it was a bad point.

This was actually the breakdown of the company. We had a 1,000 units produced of that small module. We had the Nuke, which was like a hardware dongle for the software. It had that little stick at the center, and this was working together with the software on the screen and we wanted to sell it for 800 Euros. We had a 1,000 units.

This was actually the breakdown of the company. We had a 1,000 units produced of that small module. We had the Nuke, which was like a hardware dongle for the software. It had that little stick at the center, and this was working together with the software on the screen and we wanted to sell it for 800 Euros. We had a 1,000 units.

The company that forced us to really proceed wanted money back from us. They simply took those instruments that they had built and they sold some for a ridiculous low money to the music store in Germany so that brought us actually out of business.

It was like that. They wanted their money and they took the chance and they sold the 1,000 units.

That was our last chance to keep on going with the company, which didn’t work out in the end. But it’s like that, you know?

Darwin Grosse: I’ve been involved in some companies that haven’t gone so well and for me it was personally devastating. You actually seem to be feeling pretty okay about it.

Axel Hartmann: Yeah, what should I do?

Back then I didn’t feel okay, believe me, but you learn a lot when you do something like that. What I learned is that I’m probably not the right person to do something like that because I’m probably too nice, too soft. At some points you sometimes have to be strong and simply request things from people and this is something that is always hard for me.

I don’t like conflict, so this is what I learned for myself, and it is also hard to do a project like that if you are not able to write a line of code. I’m an industrial designer. I can do a lot of things, but I cannot write a line of code. There’s a big dependency on the people that work on the code.

Darwin Grosse: Right, especially now when even analog systems have so many digital controls and digital networking functions that have to be written. I hadn’t really thought about the code dependencies being so critical but that absolutely makes sense.

This makes me wonder then, from all the broad stack of work that you’ve done (and it’s been some pretty amazing stuff), what is the design that you remain most proud of? What is thing that you always … if you die and you go up to the pearly gates and St. Peter says “What did you do that should allow you into Heaven?” What’s the synth that you would point to that would get you in?

Axel Hartmann: There’s been some that I’m really proud of, I must say, but I like the Little Phatty.

Axel Hartmann: There’s been some that I’m really proud of, I must say, but I like the Little Phatty.

I think I like it a lot because I had the chance to work together with Bob Moog in person. That was something that was a really, really a great experience.

The design was a perfect match for what Moog wanted back then. It did propel them to the place where they are now. I think that was their best selling synth.

And I think the make up was perfect. How the casing was made up, how easy it is to build, so that’s maybe one. And the Wave.

One thing that makes me very proud – if you look at GarageBand from Apple and you go to the synthesizers, you see the icons, then you see the Wave there.

Darwin Grosse: The picture of the synthesizer is the Wave.

Axel Hartmann: That makes me very proud, I must say, because there’s not a lot of options there. I think they have a Minimoog and I think they have some drum machines, and they have the Nord I think. The first one – the Nord Lead.

This is something I think: Steve Jobs brought me in there. I think this is something that I’m very proud of. This shows that the Wave was an icon that we built together. It was not only myself, it was a lot of people that worked on that and I can be proud of that.

Darwin Grosse: Indeed, so what does the future look like for you? I’m sure you’re working on things you cannot talk about, but I’m sure that you’ve worked on some things that are future for us that you can talk about.

Tell us a little about what the future looks like for you.

Axel Hartmann: There are some things I’m working on right now which I cannot tell anything about, even if they are on the very brink and soon they will come on the market.

I think the future for me is a deeper interaction with software and hardware. It’s something that Arturia has been doing with their products, and then there’s the Eurorack market, I don’t know. If it’s on the brink, if it’s going down again, but it looks like it’s still on a good swing, so I await that maybe there’s more products coming out that maybe link the Eurorack world into the world of real musicians.

There are people that I think want to make more use of the system than just ‘bling, bling, bling’. I think there’s a lot of things in the future that may be coming out of that.

Maybe also with software. Ableton is working on their side to building on the bridge between software and hardware. That’s very interesting and exciting stuff that’s going on there.

Darwin Grosse: Are you still involved with working with Waldorf?

Axel Hartmann: Sure, yeah.

Darwin Grosse: Were you involved in the new Waldorf keyboard with space for Eurorack modules?

Darwin Grosse: Were you involved in the new Waldorf keyboard with space for Eurorack modules?

Axel Hartmann: Yes.

Darwin Grosse: It kind of has your fingerprints on it.

It looks like your work in that it’s a beautiful design, it’s kind of priced right, but it kind of harkens back to what you said that you’re a player so you like thinking in terms of playing rather than some kind of generative system.

I think that that Waldorf thing really looks like a device to take Eurorack stuff and allow a player to have access to it, right?

Axel Hartmann: Yeah.

Darwin Grosse: How do you imagine doing that same kind of thing with software? We’ve seen places where they build a computer and a big touchscreen into a keyboard and they’re kind of huge. They look like big aircraft carriers or something and not necessarily like instruments.

How do you imagine taking computing devices and really allowing them to feel like instruments? That seems to me like a really hard design challenge.

Axel Hartmann: It is, but there’s new technology in the world if we’re talking VR, AR. There’s new things on the horizon that may help to interact in new ways: in combining visuals that you virtually see in front of your eyes that interact with hardware that you can really touch. I think there’s a lot of cool things that can be done with that type of technology, especially in the interaction with real world elements. This is something that I and some of my people here at Designbox can see a lot of potential for future instruments and future interface ideas.

Darwin Grosse: That really sounds exciting. Axel, I look forward to seeing the things that you come up with. Every time I run across one of your designs, I’m charmed.

And it does make me want to jump out of my seat and spend some money. So, go slow with that. Don’t do it too fast, because I have to save up in between designs!

I appreciate the work that you’re doing. It really … it’s wonderful to have someone who’s a thoughtful designer in the musical instrument world, because it does help us to have things that feel like instruments and not boxes of technology so we thank you for that.

Axel Hartmann: And I thank you for having the chance to talk here.

Additional Resources:

- You can find out more about Hartmann and his company at the Designbox site.

- 20 Synthesizer – the home of Hartmann’s new boutique synth design

Darwin Grosse is the host of the Art + Music + Technology podcast, a series of interviews with artists, musicians and developers working the world of electronic music.

Darwin is the Director of Education and Customer Services at Cycling ’74 and was involved in the development of Max and Max For Live. He also developed the ArdCore Arduino-based synth module as his Masters Project in 2011, helping to pioneer open source/open hardware development in modular synthesis.

Darwin also has an active music career as a performer, producer/engineer and installation artist.

Images: Axel Hartmann & Designbox

Wolfgang Düren – not Wolfgang Durham 😉

Yup – we just caught that misspelling, too. Thanks.

Admin: Personal attack deleted.

Keep comments on topic and constructive.

Good read, thank you.

ahem….photo is of Microbrute btw

Thanks for the feedback!

Impressive talk. Very educational… much more interesting because Axel Hartmann is not somebody who talks very often. Btw, SSD, not SD.

Thanks for the feedback. That’s in a quote, so we left as is.

My Ensoniq ASR would have been amazing with 16GB SD drive! Eventually both the internal floppy and my ZIP drive died, moving parts bah.

People often compliment the little phatty’s design which I just take for granted now, but I do love how the pitch wheel lights up, and I love the lights display for each knob, they use that in a coffee ad now it looks so cool.

My only other comment is EVERY SYNTH SHOULD HAVE A TRANSLUCENT JOYSTICK!

And I didn’t read the rest… maybe needs to be broken up into bite size chunks?

To each their own I suppose. I think the light-up pitch wheels that appear on Moog and DSI stuff look really tacky. When I got my OB-6 (my only acquisition from either of those two companies), I vowed that the first time I open it up for anything, I’m going to disconnect those stupid LEDs.

(Come to think of it, it might have made more sense to make the wheel LEDs blue on the OB-6, to match the panel… hmmm … oh, never mind)

Great interview – it’s amazing how many awesome synths this guy has been involved with over the last 20 years. Many classics!

I love his designs, alway have.

a synth has to SOUND good, not to look good, cos it´s all about music, not about the instruments you need to make it. *facepalm*

Design is more than aesthetics, it’s also user experience. For example a good sounding synth with a bad interface won’t appeal to live musicians.

ragnhild

Are you saying that we should settle for ugly, hard to use instruments that are hard to manufacture and quickly break?

Because those are the problems that industrial designers like Hartmann help companies avoid.

Interesting interview and indeed the designs for the wave and the neuron were great. I do believe though he has the wrong idea about eurorack and with the “real musicians” bit he seems quite ignorant of a music reality.

A lot of Eurorack modules seems to be made by technicians rather than muscicians, and juding from a lot of module demos on youtube, so are many of th buyers as well.

I’ve also seen many examples where oscillators are forced to play rhytmical expression, when they are clearly designed as elements of a subtractive system, where that should come from the amp-stage. And I’ve seen exmples where the notes comes from the output of modulation, rather than any device designed to send actual pitch. I’ve seen that from both makers and from people doing demos of their modules on youtube. Suggesting that there could be a lack of knowledge about subtractive synthesis. The result can at times be quite unpleasant, even though the osc in itself seems capble as an osc (sometimes that unfortunately are the only demos one can find of a specific OSC)..

And when it comes to modular music, a lot of it is more of listening to slow parameter changes. More of a sound experience than a musical composition. Sometimes this is probably a result of the person not having a big enough system, to actually perform enough parts at once, to form compositions.

I’ve heard modulars being played with voices in mismatching rhythms. In ways I don’t think was intentional. And voices playing in different keys, different tunings. I’ve heard things that seem like unexpected interruptions, or sounds going all over the place, because the person playing seem not to know what they are doing. Inharmonic sounds are not uncommon, on trade shows, youtube demos and in the music.

So I think there is many examples of lack of skills, that due to fact that there is much experimental music made on modulars, somehow get mixed in there as experimental music, when it is mostly just a collection of attempts and accidents, perhaps starting out as a happy accident that actually sounded musical.

Non pitch quantized modules and sequencers are also trendy within the modular world, because people have heard that is what they should get, because CV and and non pitch-quantized modules and sequencers will free them from the limitation of midi (whereas is much musical use, the limitation of midi comes from resolution of control/modulation, and the quantized pitch is not actually that much of an issue, especially not if pitch-bend is used). So there is a lot of music “out of tune”, some of it intentionally and perhaps actually just in a non westen-scale, but a lot of it is out of tune, because the person controlling it, did not know how to get it in tune.

And many such sequencer lacks storage, and thus to perform songs, one would have to real-time change the settings, for every new part of the song, it does impose a limitation that people that know how to play instruments are expected not to accept. In that way those sequencers aren’t really like instruments. They are not played, they are programmed, and their interface is not designed for live changing. Sequencers can work well for backing tracks, or for playing really quick sequences that can’t really be played manually. But they make little sense as instrument interfaces. In a live situation, a lot of people expect parts of the music to be played live, not just parameter tweaked. People like Jean Michel Jarre, and Kebu uses sequencers, but they also play live.

Sometimes it is hard to tell the unskilled apart from the music made by musicians that actually knows how to program synths and to compose music, but that has chosen modular for experimental music.

It would be quite easy to get the idea that almost no one making modular music actually knows what they are doing, by the number of videos of people that don’t seem to know, and those that go too far for many musicians taste in terms of experimentation.

I think the modular community itself plays a part in not reaching to that many top producers and famous artists. Because there are few attempts to actually try to market modular as another synth approach, it seems more marketed as an alternative music tool.

I don’t know if it is intentional, that some really want modular music to be a niche, and that Eurorack modules should only be used for modular music.

Eurorack modular systems can be a way of designing custom synths that are then used for any type of genre as a pre-built synth would.

But it is rarely seen in such situations. There are some exceptions.

So threre is a huge risk that someone that is trying to explore the idea of eurorack and modular for the use in music, finds demos and modular music that can be quite off putting, instead for seeing how it can be used for any type of music just like other synths.

But there are lots of bad demos of “self-contained-synths” as well… but “self-contained-synths” are established as instruments, whereas a lot of people think that modular is something very different from “self-contained-synths” (some are though), and a youtube search would lead them to that conclusion or confirm that view.

But the same can be true for certain specific self-contained-synths as well. Many demos of Arturias brute series doesn’t present them in a context where they fit in typical music. But those are not the only synths suffering from that. And there are also some synths on the used market that suffer, and since there is no money or no large number of clicks and likes to be made from making videos of used synths that may be hard to come by, so there isn’t a huge interest in that particular product, that is no wonder. And a lot of demos of used synths I have seen are made by people that lack programming skills, and many don’t even play anything, just presses a few keys, so there is sound, suggesting that they perhaps can’t play keyboard and even when there is midi, they don’t sequence any midi files, to compensate for the lack of playing skills, so pehaps there are skills missing in that area as well.

So I think the synth as an instrument would have a really hard time as well, if it wasn’t established.

It’s no wonder if some people think that eurorack isn’t for “real musicians”, when they are shown so little proof that it is.

Worth keeping in mind is also that “real musicians” is not the same thing as the only ones that can make real music. AI or even random processes can come up with real music. Real music can happen by happy accidents. Animals can perform real music… and actually even dead objects sometimes generate noises that contain harmonic content and rhythm.

Damn good interview… i appreciate his involvement with synths throughout the years… I have always loved the layout of the Blofeld… I will have a neuron one day…

Great interview. Darwin did a nice job of bringing Axel right to a good place with each question so Axel could give a complete interesting answer. Nice!